I’ve spent three weeks of my summer in rainy, rainy, rainy (yes, it has rained every single day) Gainesville, Florida as the 2025 ALSC Bechtel Fellow, where I’ve been studying the papers of Margaret Sidney, a 19th century children’s novelist best known for The Five Little Peppers series. While I’ve been reading the books, my time at the archives in the Baldwin Library of Historic Children’s Literature has mostly consisted of me going through the five archival boxes that consistent her existence here in Florida and finding new gems and treasures. I’ve transcribed short stories from 1880s newspapers, re-acquainted myself with cursive handwriting, and looked at a lot of newspaper clippings about her dead husband.

My research is on Margaret Sidney, born Harriett Lothrop, so at first I felt a little bit miffed by how much of a particular box was dedicated to her husband Daniel Lothrop’s death. He was eulogized in newspapers up and down the East Coast when he died on March 18, 1892. I browsed the ephemera of their marriage, but didn’t think much of it until my third week at the archives, when I returned to box five and unfolded folder 105, a memorabilia item labeled “Hid in the Heart.”

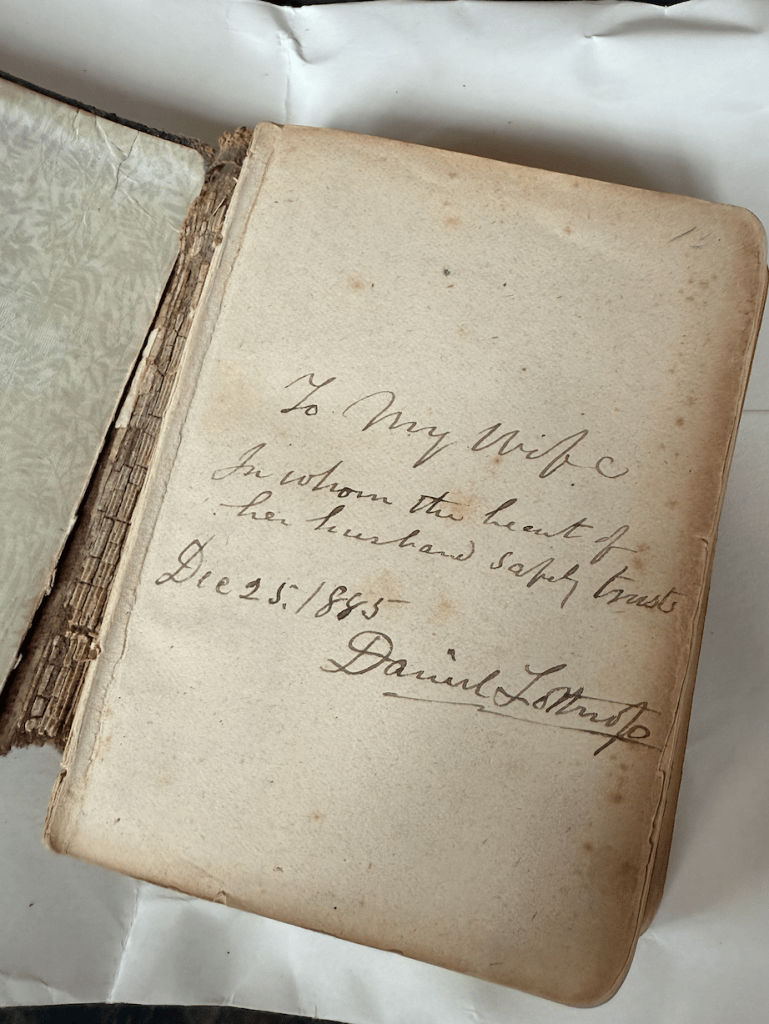

It’s a small green book, tattered because it is from the 19th century. It’s a greenish-blue color, with lots of brown spots. It’s no more than three inches tall, a little less than three inches wide, and thick with pages, over 400 of them. The top lefthand corner of the front cover says “Hid in the Heart” in a nice gold script with a little curved line underneath it. The bottom right corner features a drawing of a flower in similar gold script–a daisy, perhaps. I’m not a florist. The folder that contained it warned me that the spine was loose, and it tumbles open easily, laying almost flat, exposing the brown ribbing and fading glue of a hundred and forty years ago. My breath catches. It’s got an inscription, “To my wife: in whom the heart of her husband safely trusts”

It’s dated December 25th, 1885, and signed by her husband, Daniel Lothrop. A Christmas gift, this tiny devotional, full of daily prayers and proverbs. It’s a book from 1881, according to the preface, short bible readings for every day of the year. Each day is referenced in roman numerals, January I, January II, January III, and quickly I realize as I slowly flip though that Harriett used this as a bit of a diary in the years that followed.

January II: “Thursday 1902, Margaret returned to Smith College after vacation” (Margaret being their daughter)

January IV: “1896 Margaret joined the Old Stone Church”

January XII: 5 ½ o’clock A.M. Margaret has a cold–watching her while she sleeps. She had been so bright and patient all day”

April X: “Oh God, help me thus be a good wife” (That day’s scripture grouping is titled ‘A Good Wife’ and references Proverbs 31)

I look through the whole thing with a cursory glance at first, noting some of the dates, all the way up to 1906. There are swaths of pages without any added writing or diary entries on them at all–it reminds me of New Years’ Resolution, and how in the spring months, she may not have been reading this daily and making her notes like she intended. She notes dates that she and Margaret arrived abroad in Southhampton, and when she visited York Cathedral.

At one point, the book simply guides me to March 18th, and I almost immediately want to cry.

“In memoriam” is scrawled across the top of the page. “Friday, Evening, 11.30 1892.”

It’s the day of her husband’s death.

The theme of the day is, I cannot truly believe it, ‘“Happy Death of the Righteous”

It’s a collection of scripture, including verses from 2 Kings, Numbers, and Psalms. The following verse stabs me in the soul, “Let me die the death of the righteous, and let my last end be like his”–Psalm 37.

On the side of the page, Lothrop has written in her own hand, the hand I know so well three weeks into this project, “I went down with my beloved husband to the gate of death – and came back alone.”

I felt the tears prick behind my eyes. When I returned to the book the next day, I took even more time to leaf through its gold-edged pages, and found more signs of her grief embedded in this little tome.

May 31: “1892. I am nearly ready to faint with my grief–and I tuned to my reading for the day.”

The theme for the day was “Comfort and Support in Death.”

This small little book does not align with my research topic. It doesn’t help me more fully understand her prose writing, or her desires to tell moral tales for children, or relationship to the Children of the American Revolution, but it was such a small bit of humanity that I could not stop thinking about it. This tiny book traveled with her for almost two decades after her husband gave it to her on Christmas morning–maybe she plucked it out of her stocking, or unwrapped it from brown paper. It crossed oceans with her, it offered her comfort in her grief, and it offered her a memory of him, his signature inside the cover.

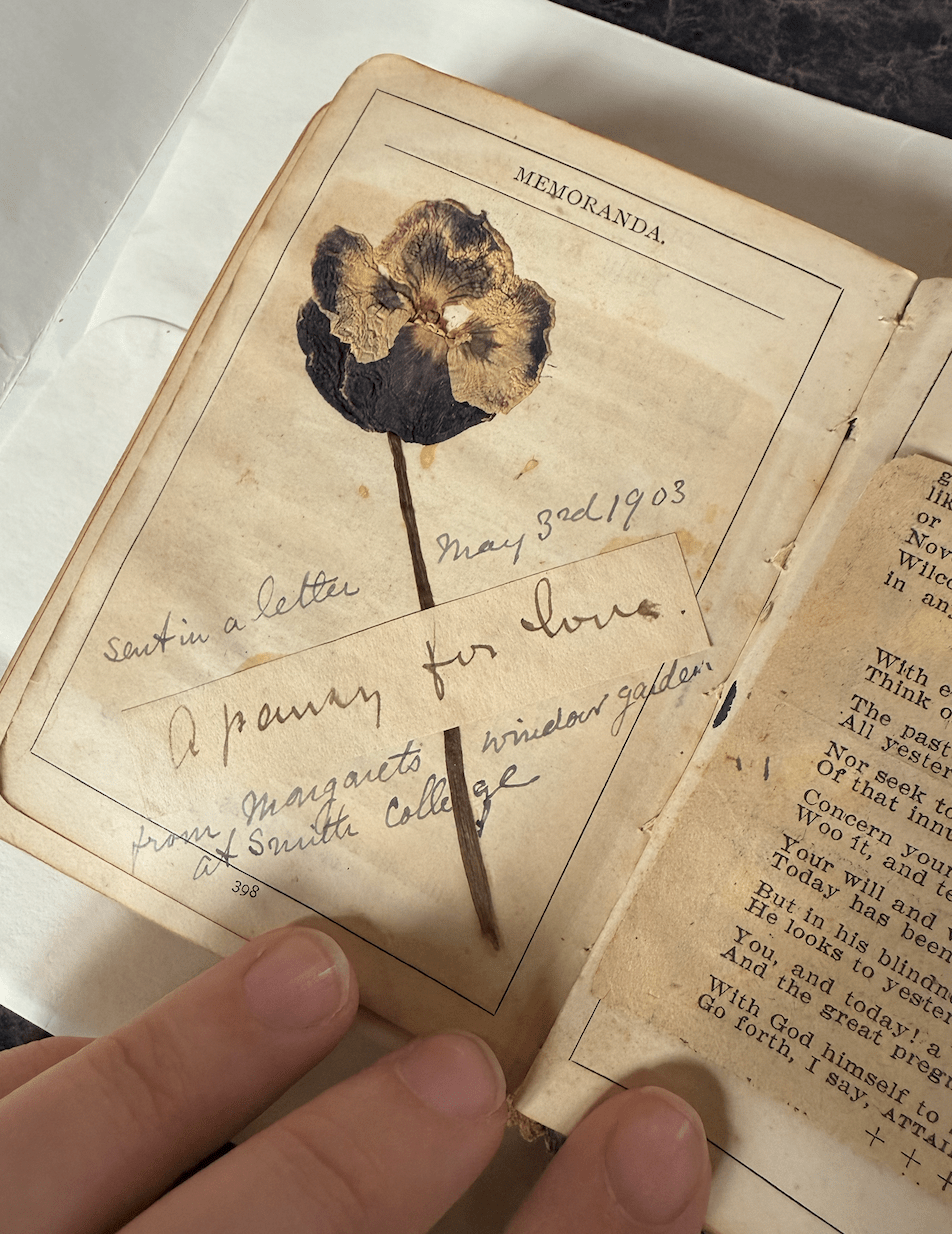

Inside the back of the book, in one of the empty pages labeled “memoranda” for notes is pressed a dried flower, with Harriett nothing “sent in a letter, May 3rd, 1903. A peony for love. From Margaret’s window golden at Smith College.”

This little book of prayers saw her through so many moments of her life–the death of her husband, their daughter going off to college–and now it sits in a little folder in the corner of box 5. I don’t know when the last time someone held it in their hands was, the last time someone flipped through it and traced the words with their fingers. When was the last time someone stopped and looked at March 18th and felt her grief on that page?

It might be the least referenced thing in my final research paper, but “Hid in the Heart” might be the archival artifact that sticks with me the longest. Archives are history, they are research opportunities, but they are also boxes of someone’s humanity, asking to be opened and held and remembered.

Leave a comment